Support Element History

Coal

Until recently, coal has been one of the most important and consistent products shipped by rail. In 2020 coal supplied about a quarter of the world's primary energy and over a third of its electricity. Long Pennsylvania Railroad coal trains were seen daily moving east from the bituminous coal fields of western Pennsylvania and the Midwest, with trains of empty hopper cars traveling west for their next loads.

Anthracite coal in the eastern part of Pennsylvania also provided significant traffic to both the Reading and Lehigh Valley Railroads.

The advent of diesel-electric locomotives and the more recent and serious concerns for the environment have diminished the business of coal hauling so it no longer has the significant role it once did, although the export market remains an important revenue source for railroads.

Not only was coal moved to ports for export and to domestic power plants, manufacturing facilities and cities (for commercial and home heating), it was also in great demand by the railroads themselves for steam locomotive fuel. Railroads employed coal towers or tipples to supply their locomotives with fuel (see photo below). On long-distance runs, trains would have to be re-supplied from such devices installed at strategic points along the line.

Water

In the steam era (1804-1980), water for locomotives was a vital resource. Steam locomotives converted many thousands of gallons of water to steam on every trip. Thus, it was necessary to provide water along the right of way, as well as at railyard servicing facilities (see photo below). Water tanks were common sights in remote areas and track pans that permitted water to be scooped up by moving trains were installed and used by some railroads. Wells and remote reservoirs were also owned by railroads to supply water to their steam engines.

Turntable and Roundhouse

The combination of turntable and roundhouse made an effective servicing facility for steam locomotives. The turntable was needed to properly orient locomotives with respect to the direction their trains would be traveling. It also allowed many maintenance tracks to be located as spokes around the turntable. The roundhouse was located around the turntable to provide interior spaces for inspections, servicing, and repairs. Roundhouses varied in size from two or three stalls, to as many as fifty or more.

With the advent of diesel locomotives, turntables became unnecessary because diesel locomotives were bidirectional in operation and did not need to be turned (reversed). Roundhouses were eventually replaced by shops with tracks that run through the facility.

An example of a turntable/roundhouse facility may be found on the Shannondell Model Railroad, illustrated below.

Railroad Signals

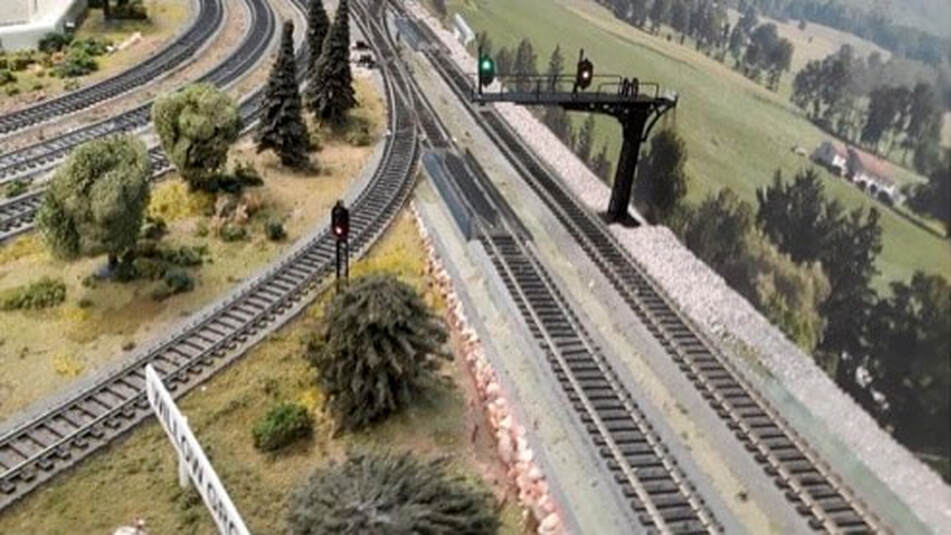

Railroads use signals to control train traffic on most of their lines. These signals tell the engineer if the train may continue into the next block (segment) of track and at what speed it may proceed. Several types of signals may be used; semaphores, position lights and/or color lights. The Shannondell Railroad uses color light signals. A red light indicates that the train must stop prior to reaching the signal. A green light indicates that the train may proceed into the next block at the maximum speed authorized for that block, usually 45 mph. A yellow light indicates that the train may proceed at medium speed (30 mph), but must be prepared to stop at the next signal. The signals are controlled based on the occupancy of other trains in the blocks ahead and on the alignment of turnouts controlling access to the block. For more detail on signals, go to Railroad Signal Systems.

An example of signals on the Shannondell Model Railroad is shown in the following illustration.

Special Cars and Facilities

Livestock Cars

Livestock, such as cattle, sheep, hogs, horses (and other equines), poultry, fish, oysters and almost anything else were usually bred and raised far from population centers. Some livestock were driven in herds to remote rail heads and others perhaps raised near sidings where the animals were loaded into cars specially built and fitted out for them.

Federal law, in effect since 1873, has required that, after 28 hours in the cars, the animals must be unloaded, fed, watered and rested for at least five hours before continuing the trip. Thus, many railroads built special facilities for this purpose along the routes of these trains. After arrival at their destination the livestock were unloaded into stock yards or other facilities, then rested and fattened before their slaughter.

As an example, a special farm in Chester County, the King Ranch, was used for this purpose by a large Texas cattle operation. Chicago had the largest such facility in Union Stock Yard & Transit Co.

In recent years the trucking industry has taken over much of the transportation of livestock.

A small cattle facility with livestock cars and cattle pens on the Shannondell Model Railroad is shown in the following photograph.

Perishable Freight and Refrigerator Cars

Almost from the beginning of the age of railroads, large quantities of vegetables, fruit, and meat have been moved across the country by rail from their source to the marketplace. Avoiding the spoilage of these shipments has always been a priority for the railroads involved.

At first, wood-insulated refrigerator cars were developed with ice bunkers at each end. Simple fans driven by friction rotors against the car wheels circulated the cooled air through the cars. If their destination was relatively nearby (< 400 miles) the ice would not melt and a reasonably cool temperature could be maintained. These cars were pre-cooled with ice loaded into the bunkers through hatches on their roofs before loading their cargo.

Teams of workmen loaded freshly cut blocks of ice weighing up to 300 lbs. In the "old davs" the ice was cut from lakes and rivers in the winter and stored in heavily insulated buildings for use throughout the year.

With the advent of mechanical refrigeration, the icing plants changed and began making ice at the site of use. Ammonia was the most common refrigerant. Ice cooled cars continued to operate into the 1960s. More recently, mechanical refrigeration units with eco-friendly refrigerants have replaced the ice bunkers in the cars and the need for icing plants.

An icing plant is modeled on the Shannondell Model Railroad, as shown below.

At first, wood-insulated refrigerator cars were developed with ice bunkers at each end. Simple fans driven by friction rotors against the car wheels circulated the cooled air through the cars. If their destination was relatively nearby (< 400 miles) the ice would not melt and a reasonably cool temperature could be maintained. These cars were pre-cooled with ice loaded into the bunkers through hatches on their roofs before loading their cargo.

Teams of workmen loaded freshly cut blocks of ice weighing up to 300 lbs. In the "old davs" the ice was cut from lakes and rivers in the winter and stored in heavily insulated buildings for use throughout the year.

With the advent of mechanical refrigeration, the icing plants changed and began making ice at the site of use. Ammonia was the most common refrigerant. Ice cooled cars continued to operate into the 1960s. More recently, mechanical refrigeration units with eco-friendly refrigerants have replaced the ice bunkers in the cars and the need for icing plants.

An icing plant is modeled on the Shannondell Model Railroad, as shown below.

Railway Express Agency

Prior to 1913, the U.S. Post Office Department (USPOD) was not allowed to ship packages within the U.S. (although it did operate Parcel Post with other countries), only letters. So, several private companies started providing express package delivery services. Their primary method of transport was to load packages into box or reefer cars that were added to passenger train consists.

During World War I (1914-1918), these express companies, the largest of which was American Express, were merged into the Railway Express Agency (REA) by the U.S. Government to better support the war effort. REA was owned by 86 railroads in proportion to the express traffic on their lines.

After 1940, REA concentrated mainly on express refrigerator service, as well as other packages. With the establishment of the interstate highway system and fast growing private automobile ownership, passenger train service declined dramatically. REA struggled to continue service until 1975.

A REA facility can be found on the Shannondell Model Railroad layout as seen below.

During World War I (1914-1918), these express companies, the largest of which was American Express, were merged into the Railway Express Agency (REA) by the U.S. Government to better support the war effort. REA was owned by 86 railroads in proportion to the express traffic on their lines.

After 1940, REA concentrated mainly on express refrigerator service, as well as other packages. With the establishment of the interstate highway system and fast growing private automobile ownership, passenger train service declined dramatically. REA struggled to continue service until 1975.

A REA facility can be found on the Shannondell Model Railroad layout as seen below.

Classification or Marshalling Yard

A classification yard (see Yard under Education) is an arrangement of tracks which are used to sort freight cars according to their intended destination, the next node of operation, or interchange. Inbound trains are directed onto arrival tracks from which the cars are then moved to various classification tracks. This may be done with a "hump" in which case the cars are pushed over a small rise and allowed to coast onto the various tracks, or alternatively, the cars may be "flat switched" in which case they are moved by a switching locomotive to their assigned class tracks.

After classification, the cars are assembled into trains on departure tracks before being dispatched to the next point of classification or destination. In addition to the classification tracks, each classification yard may have several arrival and departure tracks, as well as relay tracks where trains may be re-crewed and sent on without classification. If the yard is bi-directional, e.g., eastbound and westbound, there may be two sets of the facilities as described above that mirror each other.

Although Shannondell Model Railroad does not have a formal classification yard, it does have a staging yard where trains may be made up manually, as seen below.