Locomotive History

The history of some real-world railroad elements, such as particular locomotives, railroad cars and selected support elements, that are represented in the Shannondell Model Railroad, is presented here. For more information on motive power used by railroads, please consult the Education section of this website.

Steam Locomotives

We have several steam trains chugging along the tracks, and the sound of releasing steam, the blast of the whistle, and the clanging of the bell are positively captivating. Here we present the history of three heavily-used steam locomotives, the Mikado, the Pacific Class K4 and the Union Pacific 4-8-8-4 Big Boy.

Mikado

One important steam locomotive is a Mikado which has a 2-8-2 wheel configuration (one leading axel with two wheels for negotiating curves, eight drive wheels for hauling heavy freight trains and one trailing axel with two wheels that gave support to the fire box). The class name ‘Mikado’ originated from the first large group of 2-8-2s built by Baldwin Locomotive Works in 1897 for use in Japan. This wheel configuration was

one of the most common during the first half of the 20th century and primarily pulled freight cars throughout the United States.

Over 11,000 of this type of locomotive were built for North American service and the Pennsylvania Railroad had 579.

The Canadian Pacific Railway received the last manufactured standard gauge Mikado model in 1948. By the end of 1960, most all of the railway companies had switched to diesel or electric locomotives, and the steam locomotives were headed to the scrap yard.

Although very few steam locomotives escaped being melted down after the introduction of diesel locomotives, there remains a Mikado L1 at the Railroad Museum of Pennsylvania waiting to be restored. It is PRR No. 520, and sits in the

open yard. Presently there is no time line for its restoration.

Pacific Class K-4

Another steam locomotive represented in the SMR collection is a Pacific Class K-4 which has a 4-6-2 wheel configuration. K-4s pulled the fastest and most prestigious passenger trains of the Pennsylvania Railroad. Some 425 of this type of steam engine were built between 1914 and 1928, by PRR Altoona Works (350) and Baldwin Locomotive Works (75). PRR No. 3750 was built in 1920 at the Juniata Locomotive Shops in Altoona, PA and was in service until 1957 when steam operations were shut down in favor of diesel locomotives. The Juniata Shops continue diesel-electric locomotive manufacturing and repair today.

Another steam locomotive represented in the SMR collection is a Pacific Class K-4 which has a 4-6-2 wheel configuration. K-4s pulled the fastest and most prestigious passenger trains of the Pennsylvania Railroad. Some 425 of this type of steam engine were built between 1914 and 1928, by PRR Altoona Works (350) and Baldwin Locomotive Works (75). PRR No. 3750 was built in 1920 at the Juniata Locomotive Shops in Altoona, PA and was in service until 1957 when steam operations were shut down in favor of diesel locomotives. The Juniata Shops continue diesel-electric locomotive manufacturing and repair today.

There are only two remaining K-4s in existence. One is No. 3750 which can also be seen in the open yard at the Railroad Museum of Pennsylvania in Strasburg, PA and the other, No. 1361, which is currently being restored at Steamtown in Scranton, PA. Pacific K-4 locomotives No. 3750 and No. 1361 were designated “The Official Steam Locomotives of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania” by the Pennsylvania State Legislature and Governor Robert Casey in 1987.

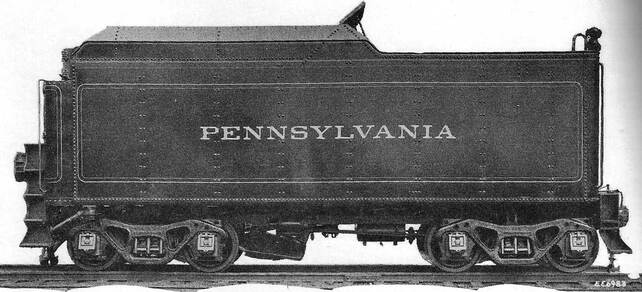

The Tender

Steam locomotives were fueled by wood, coal or oil. The choice depended on the availability of the fuel and its cost compared with alternatives. Of course, the locomotive had to be designed to burn a given type of fuel.

Locomotives were typically designed to operate with a tender, a car designed to carry fuel and water to supply the locomotive as needed. Many designs were used, but the basic idea was a box for wood or coal or a tank for oil and a separate tank for water. Tenders were either separate cars coupled to a locomotive or else integrated into the locomotive. Below is an example of a separate tender.

The Doodlebug – a Gas-Electric Rail Car

The “Doodlebug’ was the common name for a self-propelled railroad car. Such a coach typically had a gasoline-powered engine which provided electricity to traction motors on the vehicle which, in turn, drove the axles.

The Doodlebug was an early solution to a thorny problem. The railroads were legally required to provide passenger, mail, and express service, but on low-traffic branch lines, using a steam locomotive and regular heavy-weight equipment was a money-losing proposition. With the founding of the Electro-Motive Corporation in 1924, self-propelled cars were produced featuring a body based on standard passenger cars, an electric transmission derived from proven streetcar technology, and a relatively powerful gasoline engine.

Doodlebugs sometimes pulled an unpowered trailer car, but were more often used singly. The design was quite adaptable to carry passengers or mail freight as the service area required and these gas-electric cars became one of the main providers of branch-line service.

The Doodlebug was an early solution to a thorny problem. The railroads were legally required to provide passenger, mail, and express service, but on low-traffic branch lines, using a steam locomotive and regular heavy-weight equipment was a money-losing proposition. With the founding of the Electro-Motive Corporation in 1924, self-propelled cars were produced featuring a body based on standard passenger cars, an electric transmission derived from proven streetcar technology, and a relatively powerful gasoline engine.

Doodlebugs sometimes pulled an unpowered trailer car, but were more often used singly. The design was quite adaptable to carry passengers or mail freight as the service area required and these gas-electric cars became one of the main providers of branch-line service.

Rail Diesel Cars

With the decline of passenger business in the 1950s, railroads looked to reduce expenses with shorter trains particularly for local and commuter operations. The Budd Company, a Philadelphia based car builder, responded with the Rail Diesel Car or RDC, a light weight, self-propelled, bidirectional, railcar that could be operated in trains of several cars or singly by one engineman. In the past similar vehicles, powered by steam and early internal combustion engines (see Doodlebug, above) had been developed. The so called "doodlebug" was one such car. But none ever achieved the level of acceptance of the RDC. Between 1949 and 1962, a total of 398 were built for railroads in the US and worldwide. The Pennsylvania Reading Seashore Lines bought twelve RDCs for use between Philadelphia and the New Jersey shore.

Shannondell Model Railroad operates a RDC on its layout, as shown below.

Diesel Locomotives

Shannondell Model Railroad has several diesel-electric locomotives available for operation on the layout. By the mid- to late-1940s, steam-powered locomotives were quickly being replaced with diesel-electric locomotives, because these engines were considerably more efficient, much cleaner to operate and were much easier to operate and maintain.

Diesel-electric locomotives burn fuel to drive a diesel engine that drives an electric generator or alternator. The electricity produced (either DC or AC) drives electric motors that turn the axels and thus the wheels. Because electric motors can develop full torque at 0 RPMs, power to move a train is available instantly, rather than having to be built up over time. For more detail, see Education.

EMD-E8

Although diesel-electric locomotives were first developed as early as 1900, it was the improvement of diesel engines, driven by World War II, that made them attractive for rail use. One of the workhorses that entered service around 1950 was the EMD-E8, built by General Motors' Electro-Motive Division (EMD, now Electro-Motive Diesel). The E8 was a 2,250-horsepower (1,678 kW) locomotive used for passenger service. A total of 450 E8A units, were built from August 1949 to January 1954.

Shannondell Model Railroad has two E8s from the Pennsylvania Railroad (PRR). Locomotive No. 5713 is shown below.

Although diesel-electric locomotives were first developed as early as 1900, it was the improvement of diesel engines, driven by World War II, that made them attractive for rail use. One of the workhorses that entered service around 1950 was the EMD-E8, built by General Motors' Electro-Motive Division (EMD, now Electro-Motive Diesel). The E8 was a 2,250-horsepower (1,678 kW) locomotive used for passenger service. A total of 450 E8A units, were built from August 1949 to January 1954.

Shannondell Model Railroad has two E8s from the Pennsylvania Railroad (PRR). Locomotive No. 5713 is shown below.

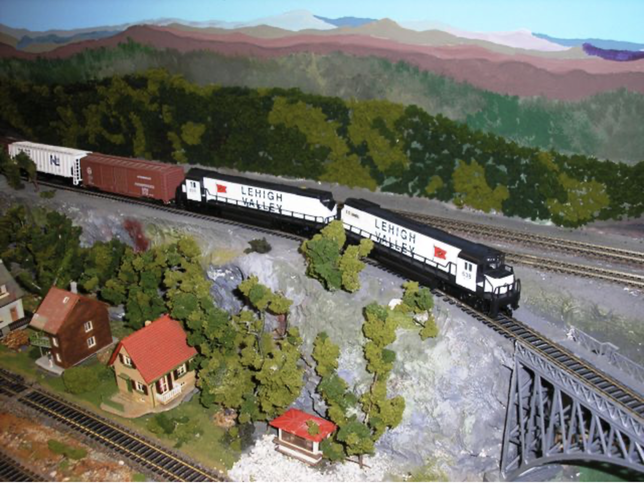

ALCO Century 628

Shannondell Model Railroad has two ALCO (American Locomotive Company) Century 628 diesel-electric locomotives in its roster, representing the Lehigh Valley Railroad (see later in this section). The ALCO Century 628 was a six-axle, 2,750 hp (2,051 kW) diesel-electric locomotive. A total of 186 of these locomotives were built during the years 1963-1968.

The two models of the Century 628 in the SMR roster are shown below.

Shannondell Model Railroad has two ALCO (American Locomotive Company) Century 628 diesel-electric locomotives in its roster, representing the Lehigh Valley Railroad (see later in this section). The ALCO Century 628 was a six-axle, 2,750 hp (2,051 kW) diesel-electric locomotive. A total of 186 of these locomotives were built during the years 1963-1968.

The two models of the Century 628 in the SMR roster are shown below.

There are two full-scale locomotives remaining, located at the Yucatán Railway Museum (Museo de los Ferrocarriles de Yucatán). One is Ferrocarriles Nacionales de México No. 610 (formerly Delaware and Hudson No. 610) and Ferrocarriles Nacionales de México 606 (formerly Ferrocarril de Pacifico 606). The condition of these locomotives is not known.

Electric Locomotives

Electric locomotives differ from steam or diesel-electric locomotives in that the prime mover is electricity delivered to the locomotive either via electrical cables or a third rail.

Subway trains, for example, run almost exclusively on electrical power because of the need to keep the air in the underground sections of the railroad free of exhaust gases and soot.

Above-ground trains usually are not so restricted, but electrically-powered trains are less expensive to build, more efficient than any other power source, offer significant operating efficiencies, reduce maintenance costs (of both locomotives and rails) and are much quieter.

The disadvantage of electric locomotives is the high initial infrastructure cost. Electric lines must be installed, along with various operating and control elements. Also, in the United States, property taxes are higher if a rail line is electrified. As a consequence, most railroads are reluctant to move to electric motive power.

Electric locomotives differ from steam or diesel-electric locomotives in that the prime mover is electricity delivered to the locomotive either via electrical cables or a third rail.

Subway trains, for example, run almost exclusively on electrical power because of the need to keep the air in the underground sections of the railroad free of exhaust gases and soot.

Above-ground trains usually are not so restricted, but electrically-powered trains are less expensive to build, more efficient than any other power source, offer significant operating efficiencies, reduce maintenance costs (of both locomotives and rails) and are much quieter.

The disadvantage of electric locomotives is the high initial infrastructure cost. Electric lines must be installed, along with various operating and control elements. Also, in the United States, property taxes are higher if a rail line is electrified. As a consequence, most railroads are reluctant to move to electric motive power.

Pennsylvania Railroad GG1

The Shannondell Model Railroad has several PRR GG1 electric locomotives, although they do not fully model the real thing. A GG1 has pantographs mounted atop the locomotive that collect 11,000 volt, 25 Hz AC power from overhead catenary cables. SMR does not model this feature of the GG1.

General Electric and the PRR's Altoona Works built 139 GG1s between 1934 and 1943, with the first units entering service in 1935. A model GG1 No. 4905 is illustrated below.

The Shannondell Model Railroad has several PRR GG1 electric locomotives, although they do not fully model the real thing. A GG1 has pantographs mounted atop the locomotive that collect 11,000 volt, 25 Hz AC power from overhead catenary cables. SMR does not model this feature of the GG1.

General Electric and the PRR's Altoona Works built 139 GG1s between 1934 and 1943, with the first units entering service in 1935. A model GG1 No. 4905 is illustrated below.

Caboose History

The use of cabooses started in the 1830’s when railroads housed trainmen in shanties built on boxcars or flatcars. The addition of the cupola – the lookout post atop the car – is attributed to a conductor who discovered in 1863 that he could see his train much better if he sat atop boxes and peered through a hole in the roof of his boxcar.

The caboose served several functions, one of which was as an office for the conductor. A printed ‘waybill’ followed every freight car from its origin to its destination. The conductor kept the paperwork in the caboose.

The caboose also carried a brakeman and a flagman. In the days before automatic air brakes, the engineer signaled the caboose with his whistle when he wanted to slow down or stop. The brakeman would then climb out and make his way forward, twisting the brakewheels atop the cars with a stout club. Another brakeman riding the engine would work his way toward the rear. Once the train was stopped, the flagman would descend from the caboose and walk back to a safe distance with lanterns, flags, and other warning devices to stop any approaching trains.

Once underway, the trainmen would sit up in the cupola and watch for smoke from overheated wheel journals (called hotboxes) or other signs of trouble.

It was common for a railroad to assign a caboose to a conductor for his exclusive use. Conductors took great pride in their cars, decorating the interiors with many homey touches including curtains and family photos. Since they could also cook meals in their cars, the caboose served as a home away from home.

However, beginning in the 1880’s, technology rapidly eliminated the need for brakemen with development of the automatic air brake system. Invented by George Westinghouse, the air brake system eliminated the need to manually set brakes. The air brake was soon followed by the use of electric track circuits to activate signals, providing protection for trains and eliminating the need for flagmen. Friction bearings were replaced by roller bearings, reducing overheated journals and making visual detection by smoke an unlikely event.

Trains also became longer, making it difficult for the conductor to see the entire train from the caboose, and freight cars became so high that they blocked the view from the traditional cupola. The increasing heaviness and speed of the trains made on-board cooking hazardous and unnecessary. New labor agreements reduced the hours of service required for train crews and eliminated the need for cabooses as lodging. Cabooses, when used at all, were drawn from ‘pools’ and no longer assigned to individual conductors.

Eventually, electronic ‘hotbox’ and dragging equipment detectors, which would check moving trains more efficiently and reliably than men in cabooses, were installed along main lines, and computers eliminated the conductors’ need to store and track paperwork.

Today, the ends of freight trains are monitored by remote radio devices called Flashing, Red, End-of-train Device or "FRED". The small units fit over the rear coupler of the last car and are connected into the train’s air brake line (see image below).